Towards Lough Dan; Lough Tay.

Local Asshole Now Local Asshole With Blog: The Twisted Brain Wrong of a One-Off Man-Mental

The extract I quoted from Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter lately put me in mind of an equally rough and ready folk autobiography, that of William Hanbidge, a native of Tinnahinch in the Glen of Imaal, Co. Wicklow, who lived from 1813 to 1909. He belonged to a society for the ‘discountenancing’ of vice, which always conjured images, for me, of a nonagenarian Quaker dropping into his local pub to gurn threateningly at the local drunk. Anyway, here is Hanbidge’s account of the descent into sin of the

Straford was a prosperous little place but it was also a most abominable wicked place

The scenes to be seen of a Saturday night and on Sundays were awful.

Drunkneness, prostitution, cursing and fighting.

There were always a wordy warfare carried on between the country and town lads for the country lads when they saw the weavers would shout A dish of kailcannon and an iron spoon would make any calico weaver jump over his loom with other scurrilous epithets which the others resented very much.

All used to meet at a low public house about half a mile from the town on Saturday evenings and Sundays the sights which followed I cannot describe.

After a time the downfall of the town began.

Mr Orr found out that he could buy the calico ready wo much cheaper than it cost him to have it woven so he dismissed all his weavers who were scattered over many parts of

The slated houses which they lived in soon fell into ruin.

Mr Orr still continued the bleaching and printing business for a short time till his correspondent in

All the remaining employers had to seek work in

Thus fell

{Quotation ends}

Those in the mood for more will be pleased to know that W.J. McCormack edited Hanbidge's memoirs for UCD Press a few years back (scroll down a bit). The above picture, which I found here, is not of Stratford but nearby Valleymount. The combination of Wicklow place-names and water reminds me of a bridge I encountered there once called Pennycomequick Bridge. Or am I making that up? I can't be sure.

New from Tom Paulin: The Secret Life of Poems, an ‘encounter with some of the most celebrated poems in the language’. Starting with Anon, Wyatt and Herbert we gradually approach the choppy waters of the contemporary, and after Hughes and Larkin find the following names: John Montague, Derek Mahon, Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon, Craig Raine and Jamie McKendrick. While it’s true that Craig Raine is not demonstrably Northern Irish, though at least Oxonian, his poem has the great advantage of being called ‘Flying to

This is a discarded poem. Consider it buried hereunder.

Daytrip

Pay two visits on the same day: your first and last. ‘We’ve come on holiday by mistake.’

The view from a mile up. Then lying prostrate in the back garden. Find the correct perspective. Change it.

Don’t tell them anything. Them meaning you. Don’t tell yourself anything. Starting now.

The little rasher of overexcited loquacity in your mouth, trailing its delicate fronds of drivel. Give it the back of your hand.

Find the thing, prod it, sniff it, turn it over. It would appear to be dead.

Cheques payable to ‘Friends of the M62’.

Allow four working days for us to do what we want with your money. You’d only waste it anyway.

Champagne all round at the motorway service café, we’re walking home.

The hearses speeding again.

The world’s first telephone sex baby.

The caller has chosen to scribble your number on a shithouse wall.

In this reconstruction the role of the missing girl has been taken by the missing girl herself.

Ditches on the estate have been drained and filled with tears and lemonade.

A CCTV camera has been arrested and charged.

Kicking the ladder away before climbing up it you have effortlessly reached the top.

Don’t let’s just agree, let’s agree to the point of violence. But our vast and endless differences – no, we can’t be bothered.

Let the caption read ‘Alderman Chubb receiving the applause of the chamber for her remarks on the relationship of base to superstructure.’

I told you I’d help you find your odd socks. I lied, I lied, I lied.

Speak a swear word, the clouds form into it.

You put on a record, I dance a little, I dance a little and sing.

The man in the street when the hero runs past, bodychecked by him and shouting ‘Hey, asshole!’, every film has one – oh my God, that was me!

This gruesome weapon, requiring only a short piece of string, half a diced carrot and an old envelope –

A bumble bee flies into your mouth, beds down, stays there.

Be sick of it. Keep being sick, sick, sick. Or, if you must, rejoice.

Night thoughts of the morning train in a room in the Royal Hotel: ideas above your station.

A big yellow skip outside the front door: your transport awaits.

Your whole body covered in tattoos, have the image of the skin underneath tattooed back over them and start the performance all over again.

DNA Scientist Who Thinks Black People Are Stupid Learns He Has 16 Per Cent Black DNA, Apologises For Previous Stupidity and Racism, Blames It on His 16 Per Cent Black DNA.

I would have used this as the post title but it didn't fit.

Read the news story here.

Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter, picaresque auto-apologia with a larrikin contempt for the mere comma, agent of bourgeoisification that it is:

Dear Sir,

I wish to acquaint you with some of the occurrences of the present past and future, In or about the spring of 1870 the ground was very soft a hawker named Mr Gould got his waggon bogged between Greta and my mother’s house on the eleven mile creek, the ground was that rotten it could bog a duck in places…

{Quotation ends}

Shortly before his Euroa bank heist in 1879, Kelly occupied a farm property in Jerilderie and dictated 8000 words to his comrade in arms Joe Byrne. He had russled some 200 horses in his time, but when this was put to him at his trial he indignantly countered, ‘Who proves that?’ ‘Non peccat, quaecumque potest peccasse negare’, as Ovid might say. In the midst of the bank raid, Kelly tried to locate the editor of the Jerilderie Gazette, who he thought could be persuaded (perhaps with some of the drinks ‘on the house’ he provided for his hostages during the raid) to publish his tract, but Gill had absconded and the text remained buried until 1930.

The endless complaint of the badly used, the harried, despised Fenian:

[Captain Brooke] knows as much about commanding Police as Captain Standish does about mustering mosquitoes and boiling them down for their fat on the back blocks of the Lachlan for he has a head like a turnip a stiff neck as big as his shoulders narrow hipped and pointed towards the feet like a vine stake…{Quotation ends}

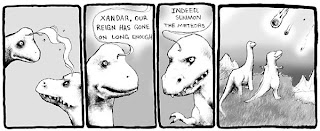

Kelly killed three policemen, but claimed that ‘a man killing his enemies was not a murderer’. At the siege of Glenrowan he came out fighting in his home-made armour. His last words before execution, myth would have it, were ‘Such is life.’ His mother Ellen lived a further 43 years, until 1923.

I marvel at Sidney Nolan’s Kelly paintings, some of which he donated to the

‘I am a widows son outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.’

Whiling away the wait for the megabucks Derek Mahon limited edition Somewhere the Wave (due any day now) with a chapter a day of Hugh Haughton’s Encyclopaedia Mahoniana.

When I finally met him myself and asked him to sign a copy of Night Crossing (still a much cheaper purchase than books two or three, Lives and The Snow Party – look them all up on abebooks and see for yourself) he somewhat theatrically averted his gaze as he signed his name. This would have been in the post-Yaddo Letter period when rumours of a proper comeback volume had the gold-dust quality of Thomas Pynchon sightings. And that book would be The Hudson Letter.

Why, for all Mahon's fascination with Ezra Pound, his Poundian (or is it Poundian?) weddedness to poetry in translation, does his Pound stop with Mauberley – as very publically signalled by the Mauberley redux of ‘A Kensington Notebook’? What would a

Introducing his translations from Jaccottet he briefly mentions Michaux and the cult of the ‘illisible’ in French poetry from mid-century or so onwards, and not approvingly either. Is this

If an early

How, when Mahon is on record as preferring the amiable enough minor poet and talisman-to-the-Irish-post-avant (no sniggering there) Thomas MacGreevy to all the poets of the Movement – not just some, all – can his reception among very-much-pro- and very-much-anti-critics in the never-ending Irish modernist debate have worked out the way it did? What are they missing? (For an example of anti-Mahon pro-modernist response, take a look at Donal Moriarty’s disparaging of

What was going on in The Yellow Book? Really, what was going on to make critics think that Oscar Wilde and 90s decadence was a useful template for denouncing the ‘fake in contemporary culture’ (that’s from an essay by Gerald Dawe, collected in his recent volume The Proper Word)? Denounce the ‘fake’ (fax machines, I remember, come in for his particular ire) by staging a love-in with Oscar Wilde?!

Connoisseurs of Irish Studies racial consciousness will have long cherished Declan Kiberd’s declaration in the Field Day Anthology that

Which of the following does Derek Mahon have most in common with: Richard Wilbur, Seamus Heaney, Paul Durcan, Thomas Kinsella, Geoffrey Hill? Award each one marks out of ten on a likeness scale. Your answers should tell you a lot about which

No promised heaven, crucified Christ,

could move me to your love, any more

than my brief default from sure hell-fire

moved me to the fear of you I missed.

You alone, Lord, move who sees

you nailed so, to your cross, and so despised:

move who looks upon your flesh so bruised,

the wounds and the contempt in which it dies.

Your love alone that moves, and moves enough

to win, though heaven never was, my love,

and though hell too be lies, my despair,

and whose cheated death – love turned to theft –

no death of mine repays, or earthy gift.

I was at a Will Self reading in a pub once, and decided I’d had enough of his aardvark-trying-to-hoover-the-fluff-out-of-its-bum voice. But the crush was too tight and, trapped at the wrong end of the room as I was, I was trapped. My only hope was a bookstall: I bought a Will Self and stood there reading it. Will Self’s voice behind me was very distracting though. My thought process was going something like this, in other words: shut up Will Self, I’m trying to read Will Self. Is there a word for a situation as ridiculous as that? If not, there should be.

Went along to a Geoffrey Hill poetry reading the other day. I noticed he pronounced Simone Weil’s surname ‘vie’ (to rhyme with ‘by’). I remember having it on the authority of someone who had met her brother that it was ‘way’ (with due allowance for French vowels). Wikipedia says ‘vay’. Is it Weil that Gillian Rose (subject of a recent Hill poem) cites at the end of Love’s Work: ‘l’amour se révèle en se retirant’? (The line is disastrously mangled in my edition as ‘en se retirer’.)

Anyway, love, Weil on love. Love shows itself in withdrawing. Love is powerless: ‘Prendre puissance sur, c’est souiller, posséder, c’est souiller (…) L’amour n’exerce ni ne subit la force; c’est là l’unique pureté.’

Love is abdication. God renounces being, shows his love for the world by withdrawing from it, and in return we must love him through renunciation and ‘decreation.’

‘Dieu a créé par amour, pour l’amour. Dieu n’a pas créé autre chose que l’amour même, et les moyens de l’amour.’

Love is an empty plenitude. I love you and walk away. I love you and never say so. I love you and we have never met.

Marina Tsvetaeva, who was hardly a model of connubial fidelity, wrote to her husband shortly before their disastrous return to Stalin’s

The last words of Kafka’s Trial, ‘like a dog’.

A tourist has just arrived in

Thanks to PMcG for this.

A correspondent to the Guardian's football unlimited page writes: 'Michael Owen has kick-started preparations for 2010 World Cup qualification in earnest by insisting none of the Croatian team would get into the

An enterprising soul has just completed his quest to visit (and sleep on) every one of

Natives of

Informed that Bonny Prince Charlie had fled to St Kilda after the battle of Culloden, crown forces travelled there to see for themselves, and found the natives ignorant not only of the prince’s existence but also of King George.

In four centuries of recorded St Kildan history, no islander is known to have fought in a war or committed a serious crime.

Mingulay, in the Bishop’s Isles, would seem a good candidate for a Paul Muldoon rhyme for ‘Mengele’, should he ever find himself in need of such a thing.

The population of

Soay, another constituent

St Brenhilda, sister of St Ronan, retreated to the uninhabited

Stanley Kubrick used the notoriously Sabbatarian island of Harris for scenes of the surface of Jupiter in 2001 A Space Odyssey. There is no connection between sabbatarianism and Kubrick's choice of Harris as a Jupiter lookalike.

Gruinard island was selected by the MoD in 1942 for an experiment into the effects of anthrax on sheep, with a view to the possible step-up from sheep to Germans, should that prove necessary. The island remained off-limits to visitors until 1990. Among the experiment's findings was that anthrax does indeed kill sheep.

A special dispensation under the Wild Birds Protection Act allows fishermen from the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis to pursue the ancient ‘guga’ hunt every year, in which up to 2000 juvenile gannets are speared and decapitated in the name of the time-honoured, disgusting diet of native North Ronans.

The three inhabitants of Gairsay, in the Orkneys, get to issue their own stamps.

The present-day remotest inhabited island in the

The

The Aids orphan and I

take a small step

to righteousness

when his face

on the charity flyer

goes not in the black bag

but one short walk

to the garden later

into the paper recycle bin.

The aged

Wait for the change in the tide where the Ouse meets the

Someone once died at a Geoffrey Hill poetry reading. I presume the cause of death would have been given as ‘misadventure’. Did GH interrupt proceedings or not? That I don’t know.

I remember an American poet once savouring his poems so much he decided to read some of them twice.

Michael Hartnett, who was a short man, once mistook an overhead projector’s lamp for a microphone and spent a reading hunched over trying to speak into it, or so I’ve been told. On hearing some giggles he straightened up and asked indignantly what the audience thought was so funny.

Jessica Smith, I have read on Silliman, distributes copies of the ‘next poem she is going to read’ before standing mutely, reading it. Some of the time. Not all of the time.

I have seen poets with their inter-poem patter written out neatly on prompt cards.

I saw a poet in York the other month receive a text message during his reading, stop to have a look, then start the poem again.

A story about Irish poet Desmond Egan’s reading style also involves Michael Hartnett. It’s been told better elsewhere, but involves Hartnett interrupting a theatrical-sounding poetry chorus staged by Egan, Hugh Kenner and Hugh Kenner’s wife, which had gone on much longer than anyone else’s reading on the same night. Very fairly, Hartnett thought enough was enough: ‘How long is this nonsense going on? Your twenty minutes are up!’

The poetry heckle. There is a story about John Montague asking his audience for requests, only for someone to shout ‘Death of a Naturalist’, but I’m sure that’s apocryphal.

There was the introducer who described a very well-known writer as a ‘fairly well-known poet’.

The Black Mountaineers' readings would go on for hours. I’ve read descriptions of Creeley and Olson readings that would only come to an end when the janitors turned off the lights and began locking up the building.

A writer once told me of asking someone who was being polite after her reading, ‘And do you write yourself?’ only to receive the answer that this was the person she had just read with.

Poetry readings. Who’d go to one, I ask myself. Who’d give one, for God’s sake. Emily Dickinson never gave a poetry reading.

North I went and west and north again: to the

Altitude in these parts cannot escape the taint of irresponsibility, every molehill tumbling straight back down again in runnels and cuttings of access roads, the dips in the road where the horizontal loses its footing.

Here worked J.R. Mortimer, disturber of dust and fossicker in graves, to produce his Forty Years Researches in British and Saxon Burial Mounds of East Yorkshire. Here too, or therein, worked Peter Riley, on his Excavations, his excavations of excavations, or burials within burials, text upon text:

the body in its final commerce: love and despair for a completed memory or spoken heart /enclosed in a small inner dome of grey/drab-coloured [river-bed] clay, brought from some distance and folded in, So my journey ended moulded in the substance of arrival I depart and a fire over the dome and a final tumulus of local topsoil benign memorial where the heart is brought to witness the exchange: death for life, absence for pain, double-sealed, signed and delivered— under all that press released to articulate its long silence, long descended • tensed wing / spread fan / drumming over the hill.

{Quotation ends}

The hillsides flecked with Aberdeen Anguses, perhaps a seasonal choice, to offset the dripping and dreepings of the hedgerows and ditches. Also a race horse, as the warning on the gate announces, a flighty mare. Mares in heat swishing their vulvas in a state of excitement are said to be ‘winking’. An English ditch, do not forget, inverts the Irish usage. Watt falls in a ditch, the better to hear the mixed chorus, but soon rises. Repeated stirrings in the undergrowth, at ground level, the busy footlings of vole or field mouse. A pocket-sized raptor strokes the air overhead, caressing the trigger and whoosh of its plunge. A woman in a small shop is bewildered by the addition of 99 and 50 pence: could it be two pounds? While the simple old man stood awaiting his ice cream, his ice cream he sat and ate in the car, his carer nowhere in sight. ‘Life Before TV’, announced the children’s tapestry in the village church, a distant prospect indeed. Then over the hill and away. Delete the photos in trying to upload them and filch one off flickr instead. A landscape of the lost. But its pebbles and cowpats are stuck in my sole, meshed and compacted. And one more time the ‘tensed wing / spread fan / drumming over the hill.’

This interview dates from 2003 and first appeared in Metre. I hope it’s still of interest.

Peter Didsbury was born in Fleetwood,

Puthwuth: Andrew Duncan has wondered on your behalf why you were “so much later than [your] contemporaries in starting, when access to print was easier in the Sixties than at any time before or since.” “Why did [you] publish [your] first book at the age of 36,” he goes on, “and why did [you] evolve so much out of touch with [your] real contemporaries, although [your] eventual technique is so easy to relate to the major poets of the sixties?” And then: “I believe, from an informant, that the answer is that Didsbury was only reading the ‘mainstream’ poets, and it took him a very long time to work out that they were uninteresting; he wrote poems in this style, which he has now thrown away.” True or false?

PD: It’s false. False spelt “bollocks”. I don’t know of any informant who would be qualified to tell him that, anyway. I started writing in the sixties, just before I left school, and a couple of poems from my undergraduate days survive in the first collection. I certainly wasn’t reading “mainstream” poets to the exclusion of anything else, or even very much. I was reading, for example, Jacques Prévert and Christopher Middleton: not people you’d describe as mainstream English poets. So I didn’t have anything like that to discard. I still have all the poems from those years and I can assure you that their faults, which are many, aren’t of the kind which come from imitation of the mainstream. And where does

P: I know that your and Sean O’Brien’s poetic beginnings were closely conjoined. How deep does that go? I’ve always thought there’s a vein of Didsbury in O’Brien, maybe especially in The

PD: Sean and I clearly were very closely involved. In fact, we first met at a creative writing workshop. Poetry was the most important thing. We enjoyed “planning an assault on the citadel of English verse” together–that’s in heavy quote marks, denoting irony… One thing we had in common is that we took the tradition seriously, wanted to be part of it, and didn’t see anything wrong with ambition. There must have been all kinds of mutual influence, we’ve been friends a long time. There’s a shared humour, for one thing, a humour of place to some extent. I can’t really comment on what there might be in my verse that would remind other people of Sean’s. That’s for them to say.

P: What do you think, at this safe distance, of the whole Bête Noire/Hull poets thing? Was it a help or a hindrance to you?

PD: You have to separate the two strands. The

P: And wasn’t Ed Dorn here too? And

PD: I believe so, though not in connection with Bête Noire. I used to be quite a Dorn fan in the mid 70s. Some of the English staff at the school where I then taught were given to attempting long monologues in American accents and cowboy personae. This would have been some years before Bête Noire. And yes, Robert Lowell came too. I believe he looked at the river

P: For a writer living in

PD: Philip Larkin means the same range of things to me as he does to most other people of my generation who read poetry. It’s nothing to do with being in

P: You’re literally a footnote to Larkin’s work, of course. Something about “sodding nonsense”, Selected Letters, footnote to p. 702.

PD: I’d reviewed some critical book for Poetry Review, and wasn’t particularly taken with it. However, I thought it really came alive at one point where the author took Larkin to task for his imperial attitudes, and said so. Larkin evidently took exception to this and wrote to Amis asking had he seen this “sodding nonsense”. That’s my claim to fame.

P: Any opinions on the post-Selected Letters, post-biography controversies? People still get very worked about all that, don’t they?

PD: Well, one always knew that Larkin was a right-winger. Some of the revelations are shocking in detail, like the songs about sending the “niggers” back home, but I think you just have to accept that he was a man of his class and generation. With a father like his, City Treasurer of Coventry in the 1920s, it’s perhaps no surprise. Sad, but there it is. This isn’t to condone anything in his attitudes, very far from it. He lived long enough to have learned better.

P: Moving on to your poetry, at last: “The Experts”, in The Butchers of Hull, features “a man who thinks he’s a Roman.” With so much Roman archaeology in your poems, I’ve often wondered if you do too.

PD: But I wasn’t an archaeologist when I wrote that poem! I suppose there are half a dozen or so poems which refer to the Roman world, but for very various reasons. In that one I was trying to evoke a vanished, rural, very local and mythic

P: “Strange Ubiquitous History” talks a lot about “our fathers” and the myths and histories they pass down. But when I think of your work alongside that of Hughes or Hill, there’s an essential difference, I think. I don’t get the same sense of investment in the blood-and-thunder, chthonic Englishness of that venerable pair. Is that fair comment?

PD: To a large extent. I’m probably much more grimly amused by the whole thing than they would be. Wary of its deceptions. I’m someone who’s constitutionally fascinated by myth and the weight of the past, but we know now where some of those roads lead. I think something like “The Drainage” is atavistic enough for anyone. It certainly frightened me when I wrote it. The poem you mention isn’t one that’s been particularly important to me but I suppose it points to some of these things.

P: On the subject of myth, you say of your “mythological characters” in “The Summer Courts” that “they continually failed me” while “In

PD: I think in the first poem the awareness is simply that people can very easily fool themselves with the mythological, while with the second… I’d just been reading the Táin Bó Cuailnge, and had a very clear synthetic vision of a kind of early-mediaeval past drawing on all the constituent heroic literatures of the

P: To come back to Hughes, do you think a writer who burrows down so deep into these atavistic forces is at risk of colluding with this mythic violence?

PD: Well, poetry’s a dangerous business. But so are a lot of things worth doing. I’m not sure it’s about the danger of collusion so much as making sure you can deal with what you uncover. I’ve just spoken about frightening myself when I wrote something like “The Drainage”. Where Hughes stood in relation to all this, how near the edge he went, I’m not in a position to say. Just to be anecdotal for a moment… when I heard Ted Hughes read in

P: If it did frighten you, were you conscious of wanting to draw back, or did you ever think of jumping over the edge?

PD: No, but it’s very strange to find out after several very intense hours or days to realize that your imagination has been telling you to write a poem about cutting animals up. The fear diminished as I examined what had been produced, what I’d been dealing with. The way we’ve been “thrown” into a world which depends on physical violence. I can look at it objectively now, but when I do it occasionally at readings I find it can still empower my voice: it can still have a disturbing effect on the audience.

P: There are other poetic

PD: It’s a darker place than Marvell’s garden. The poem mentions Marvell, but in relation to public burning, an attendant possibility in his day. And there’s an awareness of the relatively recent massive violence of the 1943 blitz. The actual garden belonged to a house in which Sean had a flat at the time. So the poem mirrors parts of the conversation and imaginings of that particular afternoon. I share the belief that “the garden” is a very proper place for the human being to inhabit, a boundary location between culture and nature, the wild and the sown. In this poem, it’s an enclosed place where I can safely indulge in some indolent imaginative speculations about Englishness and then step away from them. I suppose there are quite a few poems set in my own urban back gardens. One very prosaic reason for this is that for much of my life I never had enough money to be anywhere else. Going back to my vision of historical

P: For me, that sense of writing out of what you don’t know gets reflected in the style of The Butchers of Hull, which employs a very stop-start delivery that’s far from placid and pastoral. What about all those verbless sentences in a poem like “The Flowers of

PD: “The Flowers of Finland” is one of those few published poems which were written in my Ashbery phase, if you like to call it that. The poems by Ashbery which first appealed to me were very short ones, and I foolishly spent a couple of years trying to write longer pieces in this loose, flowing

P: Maybe related to that is “Saying Goodbye”, in which you say “The problem is how to address yourself”, or “The Smart Chair”, where you talk about not recognising your own voice. There’s a disaffection with the first-person I in your poems, isn’t there, as it’s deployed in more conventionally realist writing?

PD: Well, I would have thought there’s a fairly normal ratio between first-person and third-person narratives in my work. I suppose I speak through quite a wide range of personae, but this just seems natural to me. I never had any interest in finding a first-person confessional voice.

P: The elliptical first-person isn’t the only difficulty, though. I used to puzzle over the “Bearshit barrow elbow HIM /ATE hash arm EYE him” passage in “The Rain” until Steve Burt pointed out to me that in fact it’s Hebrew, a transliteration of the opening of Genesis. Kindly explain yourself. And according to “That Old-Time Religion” shouldn’t God be speaking Sumerian, not Hebrew?

PD: It’s a poem in which I was simply having linguistic fun. The sub-title and dedication provide the key to it: ‘Text and Exposition of a Northern Creation Fragment, for Neil Astley”. Bloodaxe was still quite a young press when I wrote it, and there was still an awareness around of its self-proclaimed ‘northern’ dimension. The whole Viking/Briggflatts thing. So I thought Neil might enjoy this spoof commentary on a spoof creation myth purporting to come from an ancient Nordic literature. There’s a lot of jokes in the poem about linguistic textual analysis, sound changes in

P: Speaking of religion, I notice that William Wootten in The Guardian objected to your claiming to have “a ‘religious’ nature”. He wanted to know what those quotation marks were doing round “religious”.

PD: He seemed perplexed about whether my claim to have discovered some kind of religious sensibility in myself was an elaborate joke, or whether it was real. Well, it’s not something I would joke about. He asked what kind of a religion it is that goes around in quote marks. I would have thought the answer to that is perfectly obvious: it’s a normal use of quotation marks, saying “religion” isn’t the best or most appropriate word, but it’s better than using that awful word “spirituality”. I don’t see any problem there. Or perhaps he wants to know precisely where I stand in the theological “realism/non-realism” debate. To which I could only answer that it’s usually nearer to the ex-Bishop of

P: There’s a strong whiff of Anglo-Catholicism in some poems, isn’t there? Have you ever been tempted, in Roy Fisher’s words, “to commit Ash Wednesday”?

PD: I committed Ash Wednesday a long time ago. I attend, with varying degrees of regularity, a church which for want of a better phrase is Anglo-Catholic. I’m all for smells and bells in the interests of helping one stand before the unknown. It isn’t part of a larger package, though, as it was for Eliot. I’m neither a Royalist nor a Conservative.

P: But then there’s a heavily pagan dimension too. Perhaps Fisher’s “polytheism without gods”?

PD: Wootten says there are plenty of pagan deities in my poems, but I haven’t counted them up. Some appear simply as props, like Anubis in “At North Villa”. In other cases, perhaps I’m just happy to personify some of those powers I find knocking round in the world.

P: As in “Eikon Basilike”. Is the Eikon Basilike figure in that poem the real hidden god of your work? And who is he anyway?

PD: There’s a seventeenth-century work called Eikon Basilike. It presents itself as meditations by Charles I, but authorship was later claimed by some

P: And more than the historical figure, is he the genius loci too, the spirit of place?

PD: He only comes in towards the end. The important figure in the poem is Cowper, for whose soul the poem declares itself to have been written. Or rather Cowper’s three pet hares, who take me on this odyssey through the frozen city. I’ve always felt rather a kinship with poor, mad Cowper, who believed all his life that he was damned. I must tell you of a rather odd incident which attaches to this poem. I read in

P: There are some poems in The Classical Farm I’ve read over and over again without coming any closer to understanding. “Glimpsed Among Trees”, for instance. But then when someone asked you to read it at your book launch the other week you said you couldn’t remember why you’d written it. Are there poems of yours that confuse even you?

PD: Yes, a few. In this case, it’s to do with what I mentioned earlier, about writing to find out what you know at any particular point. It doesn’t follow that you pay the same amount of attention to all of them after they’re written. I hadn’t read that poem in public in the twenty years since I’d written it, which meant I didn’t have a technique for reading it. Afterwards I tried to construct the remarks I should have made to ease the audience into it and I realized I did know what it was about: it was about the past of that street where I used to live, going back to when it was farmland, it was about an awareness of the river and the fog, and the nearness of the estuary. I could have said all kinds of simple things, but was too startled by the request to get them out.

P: On the subject of critical responses to your work, let me read you a short passage from “The Hailstone”: “A woman sheltering inside the shop /had a frightened dog, /which she didn’t want us to touch. /It had something to do with class, /and the ownership”. John Osborne comments: “In the twenty-first century an astute reader might deduce the entire Thatcher era from these five lines.” And David Kennedy: “The image of the woman with the dog as an apprehension of political order can also be related to postmodernism in general.” Postmodern and political: what was it about that dog?

PD: It was nothing about the dog, it was the woman. Her class neurosis was almost tangible. The other people involved in the poem, passers-by, my wife and myself, were quite joyous, as English people often are when it’s raining: it was a joyous summer downpour, we’d been running through the rain, feeling quite high, and I expected this woman to somehow share in the exuberance and joy I was feeling at the time, but she was so neurotically class-ridden. It’s quite natural to me to pet other people’s dogs in shops, to approach them through their animals, but she was terrified of this act. I think John’s comment is very valid. It seems to me to speak of the whole last century, rather than just that specific period, but the poem was written in Thatcher’s

P: Something else people get very frightened of is postmodernism. You’re adamant you’re not a postmodernist though, despite what Bête Noire used to say? Roy Fisher, to mention him again, goes all jittery when the p-word gets bandied around and calls himself a “submodernist” instead.

PD: No, not postmodernist. I share those jitters. I’ve never really understood the term, at least in the sense of knowing why it’s particularly necessary. I didn’t understand all the hype about it when it became fashionable in the late 70s. But I don’t move in academic literary circles. I wrote something for the PBS a few years ago saying I objected to the term in relation to myself, since on a very simple level I don’t think I do anything in my work that Lawrence Sterne, for example, hadn’t done before. Or is he a postmodernist too?

P: “A Letter to an Editor” hints at difficulties with getting your third book written. Do you find your inspiration comes and goes? You took even longer (nine years) with book four.

PD: It’s a simple fact about the way I write. There are very ordinary reasons which contribute to that, pressures of earning a living at different points in my life. Some quite prosaic reasons, too: The Classical Farm was finished and accepted two years after the first book, but Bloodaxe was still struggling to survive at that point and it was eventually five years before it came out. I just kept adding poems, which is why it’s quite a long collection. It was dispiriting though, and I lost some momentum. Nothing mysterious about it: Larkin’s muse went, and there are times when I’ve thought mine has gone completely. I’ve often wished I was writing more, but a book takes as long as it takes. I don’t set out to write books, I wait until I’ve got enough to put between the covers.

P: Various critics have pointed to a break in your style between your first two books and That Old-Time Religion, and the first few reviews of Scenes from Long Sleep have aligned its new section very much with That Old-Time Religion. Do your four books fall so neatly into two halves?

PD: Not quite. I think the major fault line runs through The Classical Farm. Because of the practical publication problems I’ve just mentioned, it contained quite a few pieces that would otherwise have been in the third volume. I was very aware of this when I was proof-reading the Collected. The first few reviews of the Collected seem to disagree entirely about the value of the different books and where they see the divide coming. People always make simple but erroneous assumptions, such as that the latest poems to be published were the latest to have been written. It’s not always the case, especially given the way I write: some poems might be on the stocks for several years until I get them the way I want them. The earliest poem in The Butchers of Hull was written in 1967. A couple of poems from A Natural History might easily have been placed in That Old-Time Religion. And so on.

P: But you do complicate the chronology by reversing the order in the Collected, putting the new work at the beginning and the old work at the end. Why is that?

PD: I simply agreed to a suggestion by my publisher, Neil Astley, who said he thought it would be appropriately archaeological to have the most recent work at the top and the older work at the bottom. One reviewer has said it’s an irritating contemporary habit to publish things in this order, but I don’t mind either way, frankly.

P: There’s a vein of almost sitcom comedy that’s new to That Old-Time Religion, in a poem like “An Office Memo”, as well as the more Shandyean whimsy of “The Devil on

PD: Yes, humour’s important, but I’m not always aware when I start writing a poem if it’ll have a humorous dimension or not. “An Office Memo” is just an occasional whimsy, a fact which seemed to distress some reviewers. If I reveal that it was originally typed out as a memo and passed around my colleagues at work then I’ll probably sink even further in their esteem. The humour is deliberate in a poem like “He Loves to Go A-Wandering”, where I’m really quite interested in characters who are seriously mistaken about what’s going on, like this 1950s mountaineering anorak character who believes he’s telling time through a telescope. And also the poem about the bear who thinks he’s becoming a sofa in some kind of terminal apotheosis at the moment of death. As it transpires, the poem says, he’s utterly wrong.

P: Would your poem about arctic explorers come under the same heading, their heroic but pointless endeavours?

PD: That poem’s called “Events at the Poles”. It took its shape from a doodle I did while I was sitting trying to write one night. I found myself drawing a globe on the paper with a kind of chimneyed shack at each pole. I wanted to know what was going on in them and the characters’ stories developed from there.

P: How would you introduce the themes of your new collection, A Natural History [in Scenes from Long Sleep]?

PD: Any discussion of themes is a kind of retrospective exercise. I don’t think I’m sufficiently used to it as a collection yet to know quite what’s going on. Probably it’s revealed to a certain extent in the choice of the epigraphs, particularly the one from Swedenborg. Also in the belatedly chosen title. I think we should celebrate ourselves, everything to do with us, much more as part of a unified natural whole. My friends’ dreams, mentioned in the title poem, are as much a part of a natural history as the swifts in the summer sky. We restrict the term to the animal and plant world now. Gilbert White or Richard Jefferies knew better.

P: I notice you write about slavery in “Coasts of Africa 1850”, and your friend the poet Mahdi Majid Saleh’s “forbidden country” in “Kurdistan”. Is your interest in migrations, exiles and refugees something to do with living in a port city like this?

PD: I don’t think so. It’s got a lot to do with what I felt when I was brought here as a child, that I’d been wrenched from my proper home. The first of the poems you mention was occasioned by my excitement at inheriting the documents and medals of a naval ancestor who was involved in arresting illegal slavers in the

P: Another new poem is called “Not the Noise of the World”, but instead of it aspiring to religion it ends up describing “the silence of which /all liturgies are afraid”. How is the tug of war between the secular and the transcendent working out for you at the moment, do you think?

PD: I’m trying to set light to it. Let me speak anecdotally, again. The poem was written in response to a request from the Salisbury Literature Festival. Each poet was invited to write a poem for a particular location. Mine was one of a group to be placed in the cathedral. At the time I wrote it I was exploring Unitarianism. I’ve still got a great affection for the Unitarians, but they’re excessively wordy. All kinds of denominations will invite you to partake of silence during a religious service, a silence which normally lasts around three seconds before the minister hurries on. That’s where the poem’s coming from.

P: As a pluviophile (your word) you tend to see sermons in raindrops rather than stones. In “Common Property” someone even hears raindrops on a bucket telling him in morse code to “go and eat his mother”. What have they have been saying to you lately?

PD: Not a great deal at all. It’s been a very dry summer.

P: I think they’re saying, “Peter Didsbury, write another book and don’t take nine years about it.” On an unrelated subject there are a few short prose poems in your first book, but it’s not a form you’ve revisited for a while. Why not?

PD: When I was younger I was aware of the prose poem as a form, and felt it was something available that I ought to try. I think it worked for me in a poem like “A White Wine for Max Ernst” but I just don’t seem to have thought about it using it since.

P: Are there any contemporaries for whom you feel a special affinity? John Ash, Peter Reading, Allen Fisher, Iain Sinclair… (you’ll have to help me out here)?

PD: The contemporary poet who undoubtedly had the greatest influence on me when I started out was Christopher Middleton. More recently, I don’t know. I have to confess that I don’t read a great deal of poetry any more, at least not in the sense of keeping up with what’s being published. I’ve had it suggested to me that I ought to be ashamed of this, or that I’m affecting some kind of exclusivity. In fact, it’s just a practical consequence of the ways my life has worked out.

P: What does British poetry most need now?

PD: In light of what I’ve just said, there’s little point trying to answer that.

P: Finally, since you talk about the difficulties of removing dog hairs in one of those prose poems I mentioned earlier, “A Vernacular Tale”, and since I notice you now own three cats, I was wondering–have you tried sellotape? It works a treat on jackets and trousers.

PD: Sounds like an invitation to sellotape my cats’ mouths together. They’ve a habit of sleeping on the beds, and you find yourself sneezing in the middle of the night. [Sneezes.] But that’s the snuff.